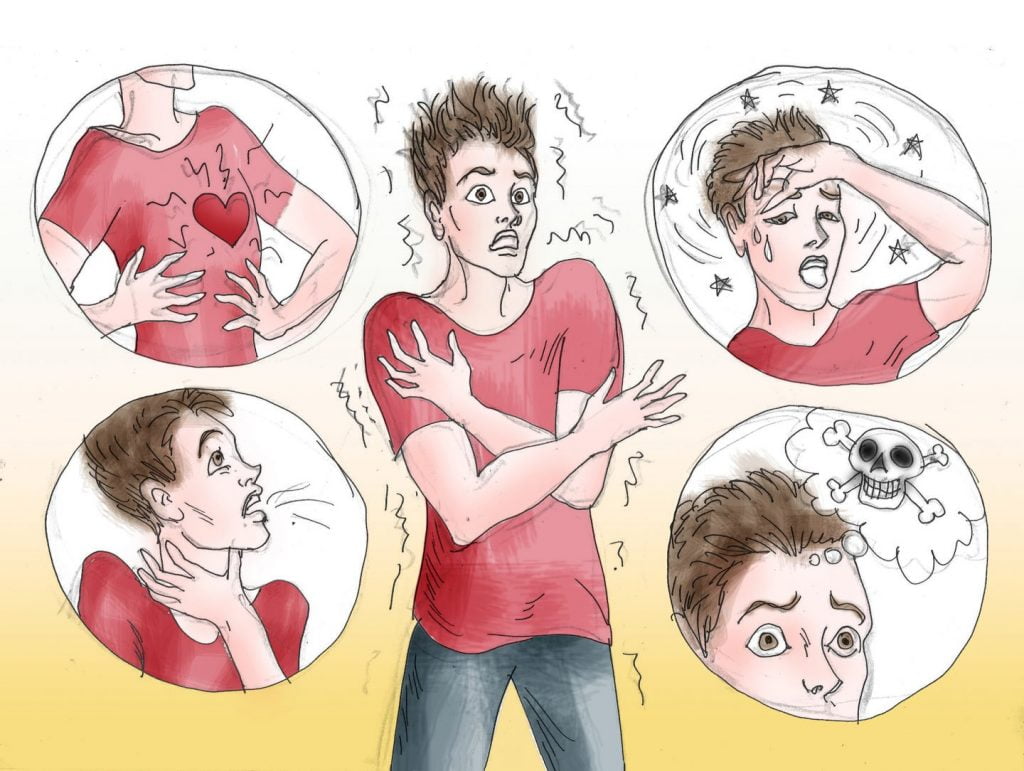

“I couldn’t breathe!”

“I felt like I was having a heart attack!”

“I thought I was dying!”

-People usually describe themselves in this way when they are having a panic attack-.

Note. Source: (Lynn, 2019)

"I feel like I am choking. I feel an urgent need to leave the area as soon as possible or something

bad will happen". - Diane

How to define Panic Attack?

A panic attack is sudden episodes of intense anxiety and fear that induces a combination of physical and psychological symptoms. Panic attacks can be frightening because they occur abruptly even when you are relaxed or asleep. They usually reach their peak in 5 to 10 minutes and persist for about half an hour. Panic onset could happen as early as the age of 12. Many people experience a panic attack once or twice in their lifetimes but frequent and repeated panic attacks might be a precursor of panic or anxiety disorder.

Sometimes people can experience increasing anxiety by just thinking of having another panic attack (i.e. anticipatory anxiety). If panic attacks remain untreated, one’s life may get impacted in a significant way. People may actively avoid places where one has previously happened or cease activities that may trigger the following attacks such as riding an elevator, using public transportation, or skipping social events, resulting in the development of agoraphobia (i.e. fear of going into public spaces or crowds).

What should I know about the symptoms of panic attack?

Panic attacks are associated with palpitations, shortness of breath, trembling, nausea, dizziness, numbness, feelings of choking, fear of losing control, and fears of dying. In addition to the typical fight-or-flight responses and extreme fears, people may experience depersonalization, which is the feeling of detachment from oneself. One may also experience derealization, perceiving the external world as dreamy or unreal.

Panic attacks are often accompanied with abnormal chest pain and rapid heartbeat that resemble the feeling of having a real heart attack. As a result, people who are experiencing their first panic attack typically ended in the emergency room (ER).

There are two common types of panic attacks. An expected panic attack occurs when responding to panic triggers or specific cues. For example, one who has a fear of blood (hemophobia) may expect to have panic attacks when seeing blood or getting blood tests. Conversely, an unexpected panic attack happens without any apparent triggers.

What are the causes of panic attack?

The causes of panic attacks are unclear. Several factors which are usually involved, including genetic predisposition, major life transitions, and extreme stress. For example, graduating from a university, starting a new job, childhood trauma or losing a loved one could potentially trigger panic attacks. Panic attacks are differentially reported among genders. More severe panic attack symptoms and agoraphobia avoidance are usually found in women.

How can panic attacks be treated?

Early treatment can be effective to reduce the symptoms and the risk of recurrent attacks. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) helps people to identify their symptoms, alter their thinking pattern and behaviours in response to the situations that trigger fears to a more realistic level. CBT allows them to be exposed to fear-provoking situations or experience the physical sensation of the attacks by using imagery, bodily focusing and voluntary hyperventilation. With each exposure, you will be less afraid and gain back control over the panic. Training in deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation techniques also allows people to calm themselves down after symptoms onset. Trivial things such as avoiding caffeine, exercising regularly (e.g. yoga) and getting sufficient good quality sleep may help release stress and anxiety. Besides, antidepressants (e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs) and anti-anxiety medications (e.g. benzodiazepines) can be used to control some of the symptoms temporarily. However, benzodiazepines may bring some unwanted side-effects.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

Emamzadeh, A. (2018). Panic Attacks: Nature, Types, and Symptoms. Retrieved 1 July 2020, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/finding-new-home/201808/panic-attacks-nature-types-and-symptoms

Huffman, J. C., Pollack, M. H. (2003). Predicting panic disorder among patients with chest pain: An analysis of the literature. Psychosomatics, 44, 222–236.

Lynn, C. (2019, September 1). Anxiety is a spirit guide; Or how I deal with panic attacks. Crystal Lynn Bell. https://www.crystallynnbell.com/anxiety-is-a-spirit-guide-or-how-i-deal-with-panic-attacks/

Goodwin, R. D., Lieb, R., Hoefler, M., Pfister, H., Bittner, A., Beesdo, K., & Wittchen, H. U. (2004). Panic attack as a risk factor for severe psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(12), 2207-2214.

Salkovskis, P. M., Clark, D. M., & Hackmann, A. (1991). Treatment of panic attacks using cognitive therapy without exposure or breathing retraining. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 29(2), 161-166.

Sheikh, J. I., Leskin, G. A., & Klein, D. F. (2002). Gender differences in panic disorder: findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(1), 55-58.

Wittchen, H. U., Nocon, A., Beesdo, K., Pine, D. S., Höfler, M., Lieb, R., & Gloster, A. T. (2008). Agoraphobia and panic. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 77(3), 147-157.